On the Amazon page for my book The Hungry Brain, the top review is positive overall but regrets that I didn’t cover the role of the gut microbiota in obesity. This reflects a common belief that differences in the microbial composition of the human gut are an important determinant of body fatness. In fact, the omission in my book was deliberate, because despite the popularity of this idea, I’m still not convinced it’s correct. In this post, I’ll review three recent findings that have added to my skepticism, including a human fecal microbiota transplant study that doesn’t mean what most people think it means. I’ll note up front that I don’t think this evidence proves that the gut microbiota isn’t involved in determining body fatness– it just proves that the hype is outpacing the science.

Finding #1

The first finding is actually a reanalysis of a seminal result in the microbiota-obesity field. The initial paper was published in the journal Nature in 2006, and to large extent, it built the field. The key experiment shows that a fecal microbiota transplant from an obese mouse to a lean (microbiota-free) mouse can make the latter gain fat. This was an important milestone because it demonstrated for the first time, apparently unequivocally, that the microbiota was actually causing part of the fattening effect– not just along for the ride. The study has been cited 5,931 times.

I’ve always been skeptical of this paper, for different reasons, but recently a microbiome researcher named Matthew Dalby took a closer look at the data underlying the claim that body fatness can be transferred via the microbiota and published the results on his blog. I won’t get into the details of his analysis– you can read them on his blog if you’re interested– but suffice it to say the finding doesn’t survive critical inquiry. The effect size is trivial and it’s likely explained by a statistical artifact called regression to the mean [Update 3/27/18: Jeffrey Walker has done a detailed statistical analysis of this experiment and shown that it is indeed likely explained by regression to the mean]. This type of anomaly is one of the hazards of using small groups of animals in your experiments (9 – 10 per group in this case), and it was exacerbated by the way the researchers chose to report the data.

This undermines a seminal finding of the microbiota-obesity field and increases my skepticism about the hypothesis as a whole.

Finding #2

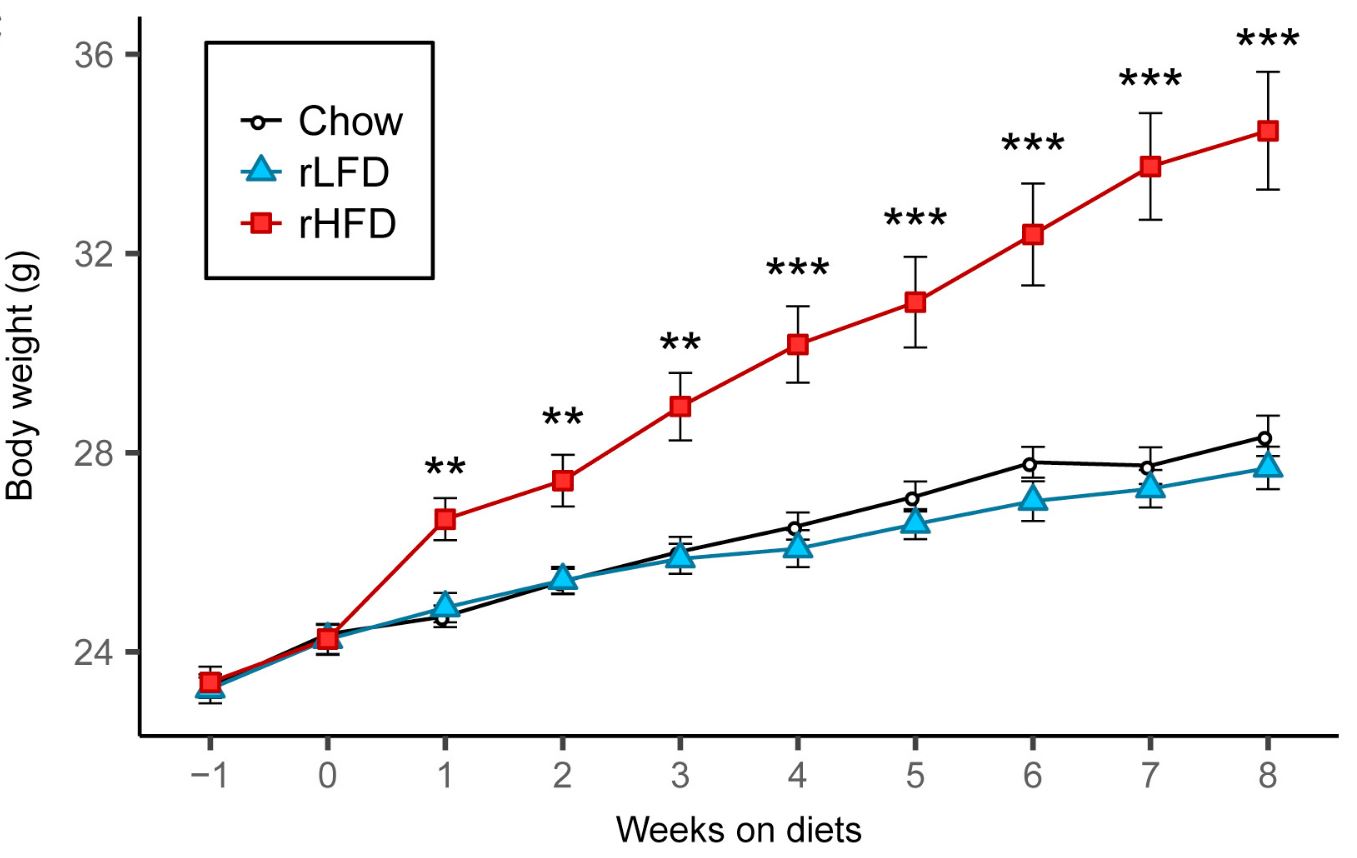

The second finding is also from Matthew Dalby, but this time in the form of a study. Published late last year in Cell Reports, the study compares body fatness, metabolic health, and gut microbiome of mice fed three different diets:

- Unrefined low-fat diet. This is the typical maintenance diet for rodent colonies and it’s primarily composed of unrefined grains and soybeans.

- Refined low-fat diet. This diet is composed mostly of refined carbohydrate, largely corn starch and maltodextrin, but also a bit of sucrose. It contains casein for protein and a few other ingredients.

- Refined high-fat diet. This is the typical style of diet that’s used to produce obesity in rodents, including in my own experiments. It’s mostly lard by calories, but also contains corn starch, maltodextrin, and a bit of sucrose. It contains casein for protein and a few other ingredients.

There are many interesting findings in this paper, but for our purposes there is one key result. The mice fed the unrefined low-fat diet and the refined low-fat diet remained lean and metabolically healthy (good glucose tolerance), while the mice fed the refined high-fat diet quickly became obese and metabolically unhealthy (poor glucose tolerance)…

…Yet when they examined the gut microbiota, it was similar in the mice eating the refined low-fat and refined high-fat diets (while the microbiota on both refined diets were quite different from the unrefined diet). Therefore, differences in the microbial composition of the gut flora couldn’t explain differences in body fatness or metabolic health.

Finding #3, or how not to analyze data and report study results

The ultimate proof that gut microbiota impacts human body fatness would be a study demonstrating that a fecal microbiota transplant from lean people to people with obesity can cause weight loss, or vice versa. The first study to examine the weight impact of a fecal microbiota transplant from lean people to people with obesity was recently published— let’s have a look.

The first place we’ll go is to the study’s preregistration site. This is the place where the authors laid out their research plan prior to conducting the study, including how the data would be analyzed an interpreted. The reasons authors preregister research plans, aside from the fact that it’s often required by quality journals, is that it shows that they didn’t tweak their analysis and reporting after seeing the data, in order to engineer a preferred outcome. This can lead to results that are convenient for the researchers but misleading for the scientific community. Preregistration is a critically important tool for combating the “replication crisis” that is currently sweeping many fields of research as we realize their findings aren’t as reliable as we thought they were.

One of the most important things a researcher should preregister in any randomized trial is the study’s “primary outcome”. This is the outcome that will matter the most for study design, data analysis, and interpretation. It is the outcome that researchers commit in advance to focusing on in the resulting publication, no matter what the results are. Researchers can also register “secondary outcomes”, which are less important. In this case, the preregistered primary outcome was “changes in weight in relation to fecal flora composition and short chain fatty acid metabolism in fecal samples after 3, 6, 12 and 18 weeks”. This isn’t very specific but it’s clear that the primary outcome is about changes in body weight. Thus, according to the researchers themselves, the study was designed and committed in advance to be primarily about body weight. Insulin resistance is listed as a secondary outcome.

Onward to the paper. The title should immediately send up a red flag: “Improvement of Insulin Sensitivity after Lean Donor Feces in Metabolic Syndrome Is Driven by Baseline Intestinal Microbiota Composition”. The title focuses on a secondary outcome but doesn’t mention the primary outcome of body weight, and the abstract does the same. In fact, the paper barely mentions that the intervention had no impact on body weight at the two reported time points of 6 and 18 weeks, and all the figures relating to it are in the supplementary materials. Let’s not be misled by this sleight of hand: the study was primarily about the impact of fecal microbiota transplant on body weight, and it found no effect.

The paper does claim that lean microbiota improved insulin sensitivity at 6 weeks, but this result is unconvincing due to poor statistical methods. I’ll relegate my discussion of this to a footnote so I don’t bore you with technical details.* I don’t know what the reviewers were smoking while reading this paper but it must have been strong stuff.

Conclusion

We still don’t have compelling evidence that differences in the composition of the gut microbiota significantly impact body fatness in humans, and the best human evidence we have suggests that it may not be important. New evidence also suggests that it may not be as important in rodents as we thought either. That said, the case isn’t closed yet. The human evidence we have is short-term, and given the staggering complexity of the microbiota and how it interacts with diet and lifestyle, there is still room for it to be important. I look forward to further research on it, but in the meantime, let’s cut back on the hype.

Thanks to Matthew Dalby for his thoughts on this post.

* They used within-group comparisons to show that the group receiving the lean-type microbiota showed increased insulin-mediated glucose uptake over the 6-week period, but the control group didn’t. They interpreted this as showing that the fecal transplant improved insulin sensitivity. The problem with this is that key statistical tests in randomized controlled trials have to directly compare between groups, not within groups. Otherwise, why bother having a control group?

Thanks for blogging on this Stephan!

If that can be of relevance, as I mentioned in a comment to one of your previous posts, I tried them all diets out there, and weight loss ensued every time, regardless of diet content (given that I did not alter my sleep pattern, nor my lifestyle overall). So my own conclusion is: CICO is THE factor determining whether one loses, maintains or gains body weight.

I also learned personally that a high fat diet can definitely be more fattening. I was already on a very low carb diet when I decided to add the so-called bullet-proof coffee to my morning routine. Not only did I feel nauseous for like one to two hours after said coffee, but I regained some unwelcome spare tire after a few weeks. That’s when i knew that these fads were all rubbish after all.

After many years of eating “normally”, I can conclusively say that it does not really matter what you eat bu how much (so long as you eat “normal foods” with enough proteins to avoid excessive tissue breakdown for amino acids) .

What CICO does is force you into looking at portion size. We’ve lost our sense of portion in the age of Whoppers. It’s not what you eat so much as how much.

In some ways I like the simplicity of the Food Pyramid. Unfortunately the Food Pyramid assumes a common understanding of what a portion is. As best I can tell a “portion” is one scoop of any food using one of those grade school cafeteria serving spoons. Maybe half a cup.

That’s exactly the problem. As I said, CICO is THE factor, but it does not really tell you much in terms of strategy.

If you are like me (i.e. not fubar), you don’t need to count anything, all it takes is a little mindfulness and a preference for REAL natural foods. It can happen that I indulge a little but it is very rare (last week, I had an amazing dinner with my wife and could hardly walk back home :D).

Result ? My weight has not moved at all. Why ? Because I keep moving everyday, and I tend to fidget more when it happens. I also saw in retrospect that I reduced my calorie intake after that dinner, without thinking about it. So sporadic excesses are dealt with.

When you are fubar (aka very high setpoint) … therein lies the problem with CICO. If you consciously reduce CI, you will feel OK during the first days or even weeks, but eventually miserable, unless you are stranded in a place for a long time where only bland foods are available. This longer term dieting would not feel unlike the weaning period of a drug addict, though I wouldn’t push the analogy too far … Now, whether this would permanently lower the setpoint of the dieter, that remains to be proven.

To my surprise, the Food Pyramid IS supposed to be connected to serving sizes. In 1999 they noted the Whopper problem:

“Consumers appear to be confused about serving sizes—-what they mean and how to use them. Complicating the problem are large portions of food that are becoming the norm in many eating establishments, which differ from the servings in the Food Guide Pyramid (FGP) and on the Nutrition Facts Label on food packaging. ”

https://www.cnpp.usda.gov/sites/default/files/nutrition_insights_uploads/insight11.pdf

Typical Food Pyramid servings are a slice of bread, a cup of milk, and half a cup of canned fruit. A big bagel, or a Whopper, confounds the whole system.

What about this recent meta-analysis?

http://www.mdpi.com/2073-4425/9/3/167/htm

Dietary Alteration of the Gut Microbiome and Its Impact on Weight and Fat Mass: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

“In summary, dietary agents for the modulation of the gut microbiome are essential tools in the treatment of obesity and can lead to significant decreases in BMI, weight and fat mass.”

It would suggest that different methods of modulating the microbiome (they look at probiotics, prebiotics and synbiotics) are at least useful tools.

Hi Robert,

That makes sense. I think I could have communicated this more clearly in my post, but I’m not arguing that the microbiota aren’t in the causal chain of body fatness or eating behavior (or even that there is no compelling evidence suggesting that). It’s more that I’m not convinced that differences in the microbiome between people are responsible for different tendencies to gain fat. I.e., the supposed “obese microbiome” that dooms some people to gain, which we theoretically could transplant and cause weight loss irrespective of diet, supplements, etc. That’s what I’m most skeptical of.

No, your post is very good. I found it really interesting. The “obese microbiome” is certainly something to be sceptical of. It’s far from that simple.

I do however think that there might be some merit in the hypothesis regarding microbiome and cravings. I.E. if you eat let’s say a high sugar diet, which in it self is very rewarding, sugar loving gut bugs will multiply. They will then make you crave even more sugar.

It maybe sounds like science fiction at first, but there are real scientists that believe in this:

https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2014/08/140815192240.htm

“Do gut bacteria rule our minds? In an ecosystem within us, microbes evolved to sway food choices”

I seem to notice these effects myself. When I hit prebiotic foods and/or supplements hard, my sugar and fat cravings seem to almost disappear. It becomes much easier to subsist on real food only, and weight drops.

Regarding sugar and microbiome, unfortunately it’s popular to give lot’s of sweets to kids, when their microbiota is being “set” during their first three years. This could, according to the hypothesis, lead to a life-long problem with sugar cravings.

But perhaps the role of the microbiome in cravings is quite small, there is a “hungry brain” also very much involved in this 🙂

My understanding was, that the “obese microbiome” theory was more about, that the microbiome has an impact on satiety and food choices. Do you have an opinion on that phrasing?

I think I have also seen some claims that differences in the microbiome lead to differences in how well certain nutrients are absorbed, but I don’t think that this could impact the caloric value of consumed food to any meaningful degree.

But look at the effect sizes reported in the meta. Eg, overall effect of any dietary modulation agent, on BMI: −0.28 (95% CI −0.43, −0.14) (note, that is mean difference, not standardised mean difference), so 0.28 change in BMI. Bodyweight: (−0.64 kg (95% CI −1.03, −0.26). Fat mass: −0.60 kg (95% CI −1.05, −0.16).

And even when you look at the effect sizes of pro, pre, syn biotics, separately, even when you look at the subgroup analysis, the effect sizes are similarly small.

Yes, the effects statistically significant, and might even be useful in combination with other methods, but hardly something to trumpet.

Yes, good point. The median duration of the studies was 12 weeks. Imagine dieting for 12 weeks, and you lose 0.64 kg. You wouldn’t be shouting about your new diet from the rooftops.

Hi Stephan – this is a nice summary and what I was looking for when I was thinking about my re-analysis of the Turnbaugh et al. 2006 fecal transplant data. All parts of this are out of my expertise except the statistics! Anyway, here is a link to the full re-analysis for any of your readers that are interests

https://www.middleprofessor.com/files/quasipubs/change_scores.html

Hi Jeff,

Thanks! I updated my post to include a link to your post.

Interesting article. Over all, I think grasping the nuance and complexity of stuff like this is key. It’s easy for people to get carried away with things like the gut microbiome (that very well could be important) and having a hard time stepping back and seeing the larger picture.

Question though: Isn’t it plausible that the diets in the study could be affecting gut health in an important way, just maybe not via changes in the bacteria themselves? For instance, high-fat diets are associated with more LPS getting into circulation, no? And isn’t the subsequent chronic, low-grade inflammatory response a possible mechanism for an effect of gut bacteria on body fatness?

Interestingly, mice being germ free seems to be protected against many of the harmful effects of a high fat diet, i.e.:

“GF mice consumed fewer calories, excreted more fecal lipids, and weighed significantly less than conv mice. GF/HF animals also showed enhanced insulin sensitivity with improved glucose tolerance, reduced fasting and nonfasting insulinemia“ https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/m/pubmed/20724524/

At the same time soluble fiber also seems to have favorable effects and will increase bacterial load. See for example: https://academic.oup.com/ajcn/article/106/6/1514/4823179

Acetic acid is the chief short chain fatty acid produced by intestinal bacteria and appears to have desirable effects. See for example: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/m/pubmed/27209492/

A study in the Japanese population found that supplementation with 30 ml vinegar over 12 weeks resulted in a 1.9 kg weight loss, compared to 1.2 kg loss for 15 ml and 0.4 kg gain for the placebo group (all groups also had 500 ml water with it). https://www.jstage.jst.go.jp/article/bbb/73/8/73_90231/_pdf/-char/en. Interestingly in the post treatment period, 4+ weeks after, the vinegar groups had gained back the weight.

Could it be that vinegar – and even soluble fiber – could lead to weight loss and other favorable effects in the short term, but even the opposite in the long term. I.e. that it is just a stimulant like caffeine, nicotine, high protein/low carb etc. Question then is what happens when the person stops taking the substance. As I’ve understood it, smokers on average have lower BMI than the general population, while ex smokers have higher BMI. Quitting smoking may lead to an average 5 kg weight gain 12 months after cessation.

I recall from the recent DIETFITS trial that while the low carb group lost more weight than the low fat group the first six months, in the next/last they gained back 1.5 kg, while the low fat group gained back “only” 1 kg. And so what would happen to many of the low carb dieters if they went back to their old higher carb diet? Would they gain back the weight and some more and be like these ex smokers? I’ve seen some low carbers and gurus looking increasingly more like drug addicts over time. Diana Schwarzbein has written much about this phenomena. It’s like Aesop’s Turtoise and Hare fable, where some gurus resemble the over confident hare who eventually loses the race.

In the long term it does appear that insoluble fiber in certain respects can be preferable to soluble and result in a slimmer figure: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0955286309000059

Question then is whether insoluble fiber and foods rich in them like whole grains and nuts “works” via a more laxative effect and less nutrient absorption partially via lower amount of intestinal bacteria. But then just taking a laxative could do the same trick (or charcoal tablets). Some people use laxatives to lose weight. At the same time as Richard Wrangham has suggested, raw foods including fruits, may also lead to less absorbed calories than cooked, partially as energy is wasted for the digestion itself. https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/full/10.1086/692113

One could imagine an alternative world where bananas was a major staple, and the food industry started to make whole banana paste, finely ground with the skin, which studies found had many health effects and reduced obesity. And one could imagine almost all nutritionist, dietitians, celebrities and so on recommended this “whole banana” which was used in breads and other products. It may not have tasted very good, but could arose other types of pleasures if the person felt he as a result of eating it would be healthier, happier and more successful in the future.

During the 19th century it actually wasn’t uncommon to add sawdust to bread, it was also used during WW1. Some scientists praised the health benefits of such bread.

guiseppe Hollywood Bread and many others in the US have wood pulp cellulose fiber added to them to reduce their calories.

http://articles.latimes.com/1985-10-09/news/mn-16819_1_high-fiber-bread

I’m not sure that sawdust is used any more. Wood pulp is food safe.

http://azdailysun.com/no-pulp-fiction-wood-pulp-is-everywhere-even-in-food/article_f1bd84a7-53f4-5930-b571-ece968237315.html

Interesting, thhq.

Should also add that it’s been suggested that calories absorbed from whole raw almonds may be about 25% less than for almond butter.

But more importantly as pointed out here https://www.google.com/amp/s/fanaticcook.com/2014/06/18/we-absorb-fewer-calories-when-we-eat-whole-foods-the-case-of-almonds/amp/

“The fat digestibility of the total diet decreased by nearly 5% when 42 g almonds were incorporated into the daily diet and by nearly 10% when 84 g almonds were incorporated into the diet daily (…) Therefore, for individuals with energy intakes between 2000 and 3000 kcal/d, incorporation of 84 g almonds into the diet daily in exchange for highly digestible foods would result in a reduction of available energy of 100–150 kcal/d. With a weight-reduction diet, this deficit could result in more than a pound of weight loss per month.”

And so I don’t know to what extent this also applies to whole grain vs refined or with soybeans vs tofu or soy milk etc, but it’s probably much less negative caloric effect in whole grains. The high amount of magnesium in whole grains may however also be laxative, as we have discussed before.

In Europe in the past it appears it was more common to consume almonds in the form of almond milk, just as soybeans were consumed as tofu or soymilk in East Asia. One obvious explanation is that they taste better. But do they taste better because the body also “knows” they supply more calories directly or indirectly, or because they are less harmful?

Staffan Lindeberg mentioned in his excellent book “food and western disease” how animals like mice, rats, birds etc which subsis on grass seeds are typically resistant to atherosclerosis when fed grain based atherogenic food, whereas primates and pigs are more susceptible. This is a reason to be concerned about the consumption of excess whole grains and probably also seeds and to a lesser extent nuts (I think the high amount of phosphorus/phytic acid and magnesium relative to calcium could be a reason for this – a reason to also be cautious about pumpkin seeds and cashew nuts – although perhaps high dose vit D can help). And then maybe the mentioned wood fiber could actually be a healthier alternative, although I’d prefer to eat tubers instead.

Charcoal is something that may be of interest to you; try and search google for charcoal and longevity. The results suggests as much as 30-100% increase in mean lifespan in rodents. I’m not sure about the validity of this research though and more recently it has been suggested to increase risk of cancer.

Dr. Guyenet,

I know most won’t appreciate it as much, but thank you so much for the footnote on the statistics.

Honestly, whiskey tango foxtrot. By having a control group, you are basically saying, “I’m going to do a between groups analysis when I’m done.”

That’s stats at the undergrad level. Doing anything else for a design like that one is just seeking out a better result.