On Monday, Wired published an article about the Nutrition Science Initiative, “The collapse of a $40 million nutrition science crusade“. This seems like a good time to review the trajectory of NuSI and what we can learn from it. NuSI was founded in 2012, ostensibly on the idea that our current understanding of obesity is at best incomplete, and possibly incorrect, and we need larger and more rigorous experiments to tease out its true causes. In practice, it was founded to investigate the carbohydrate-insulin hypothesis of obesity, the favored hypothesis of its co-founder Gary Taubes (its other co-founder is Peter Attia, MD). It was clear in early materials released by NuSI that its staff believed strongly in this hypothesis and felt that these experiments would vindicate it and address the obesity crisis. They predicted their efforts would reduce the prevalence of obesity by 50 percent, and the prevalence of diabetes by 75 percent, by 2025.

These grand ambitions, coupled with Taubes’s high-profile public advocacy stretching back to 2002, and Attia’s energy and vision, netted NuSI over 40 million dollars, almost all of it from the Arnold Foundation. In 2012, I was contacted by Taubes and Attia, who explained what NuSI was and asked for my support. As I explained in a post I wrote at the time, I ended up endorsing NuSI because I viewed it as an additional funding mechanism for testing questions related to obesity and nutrition that may otherwise be difficult to fund. Equally important, I saw that they were selecting high-quality researchers to do the experiments rather than cherry-picking people who were on the home team. I had a conversation with Kevin Hall, PhD, during which he reassured me that under the terms of the agreement, NuSI wouldn’t have the ability to tinker with study data or interpretation. More funding for interesting science, and an agreement that prevents scientific tampering. What could go wrong?

That said, I did express major reservations about NuSI at the time. Their materials suggested that they were heavily biased, and, to quote myself, “It would be remiss of me not to question the wisdom of putting a major science funding mechanism into the hands of a journalist who is, shall we say, very attached to his ideas.” Despite these reservations and my substantial uncertainty about whether NuSI would support good science or become a corrupting influence, I felt that it had more potential to do good than harm.

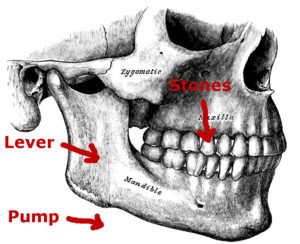

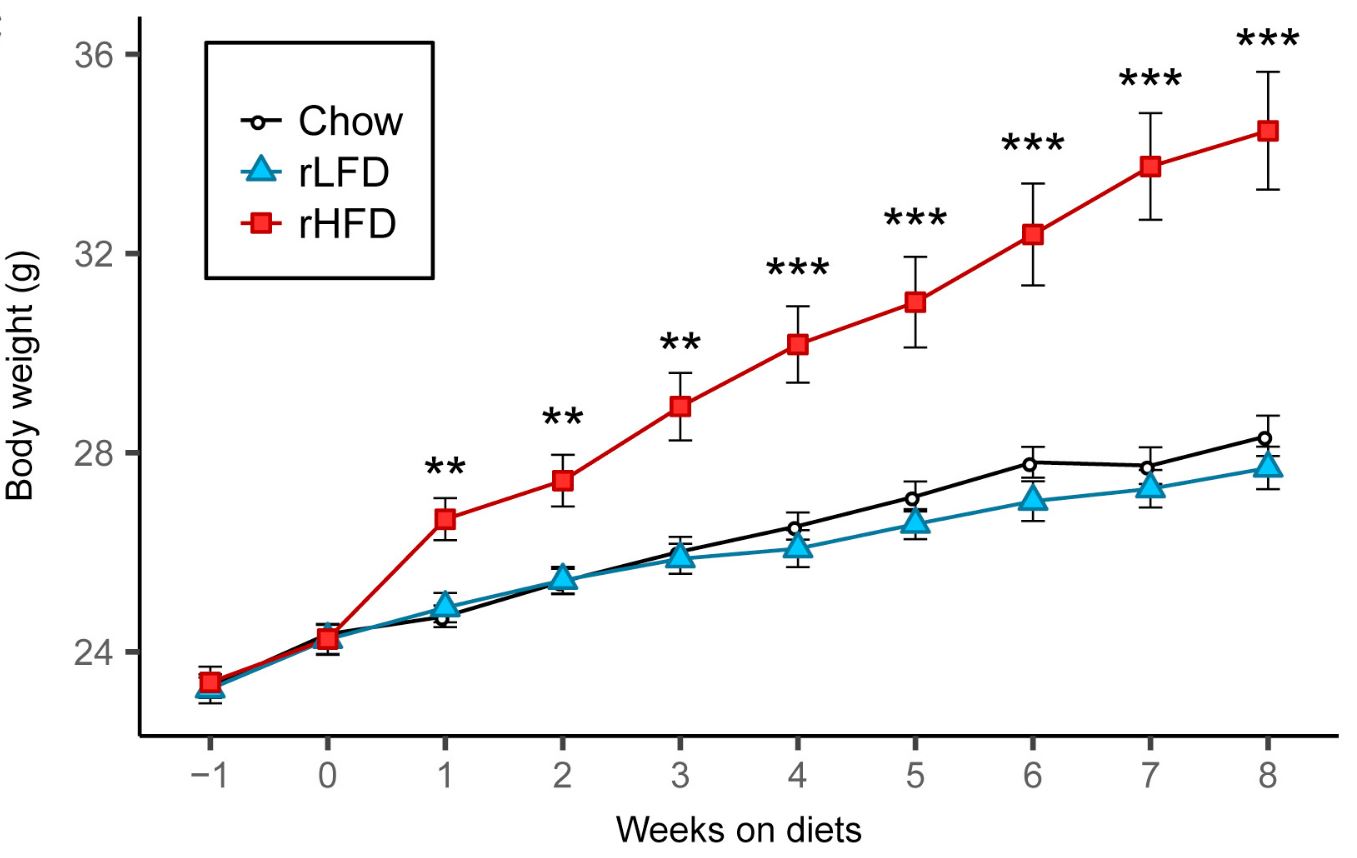

The first study NuSI funded was a meticulous eight-week pilot trial, led by Hall, to see if a very-low-carbohydrate (ketogenic) diet causes a meaningful increase in calorie expenditure vs. a calorie-matched standard American diet with more than tenfold the sugar. Volunteers were kept in a research facility where every morsel they ate was controlled. The study design was agreed upon in advance by both the researchers and NuSI, and the diets were designed by low-carbohydrate diet researcher Jeff Volek, PhD, RD. According to Taubes, calorie intake is virtually irrelevant and insulin is everything, so his hypothesis predicts large and obvious differences in calorie expenditure and fat loss between diet periods, despite equal calories. The results showed little effect of the ketogenic diet on calorie expenditure, and an initial slowing of fat loss, despite a large and persistent decline in insulin secretion.

NuSI reacted poorly to this news. They suddenly became very critical of the study’s design, and according to a timeline shared by Hall, “requested access to the data and began providing extensive comments on the data analyses and interpretation”. NuSI also requested that the researchers withdraw an abstract on the study they had submitted for the American Diabetes Association meeting, which they did. I find this particularly galling. [Update 8/22/18: the reason for this is more complex than I was initially aware of. See this post for an explanation.]

The study did have substantial limitations, most notably its lack of a true control group*. After seeing the study’s results, Taubes began arguing that these limitations make the study uninformative, reversing his initial support for its design. The truth is that, despite the study’s limitations, there is no way to reconcile its findings with Taubes’s version of the carbohydrate-insulin hypothesis. If carbohydrate and insulin do what Taubes thinks they do, the extreme difference in carbohydrate and sugar intake between the two experimental diets would have made this clearly visible. NuSI seemed to understand this before the results came in.

The interference from NuSI became so intolerable that in April of 2015, Hall and the other researchers wrote an email to NuSI asking to “reestablish the academic freedom” of the research team, as per their initial agreement. Rather than backing off, NuSI doubled down. In June of 2015 it “confirmed that it wanted to be more closely involved in the design, analysis, and interpretation” of the next study. This is documented in Hall’s timeline.

From there, NuSI entered free fall. Attia resigned in December of 2015. After a spat between Hall, Taubes, and Mark Friedman, MD in front of John Arnold in January of 2016, which presumably broke the camel’s back, Hall resigned from his NuSI-supported position. The Arnold Foundation stopped sending checks, and NuSI withered. NuSI still exists today, but most of its staff are gone and it’s limping along seeking funding. [Update 8/22/18: the reason for the collapse of NuSI is more complex than I was initially aware of. I spoke with Peter Attia and painted a more complete and accurate picture in this post.]

In retrospect, it’s not surprising that NuSI collapsed under the weight of its own ideology. The nature of ideology is that it’s inflexible when it encounters facts that contradict it**. It cannot bend, it can only break.

One thing that I think hasn’t gotten enough attention is the fact that NuSI staff, particularly Attia, paid themselves enormous salaries while they were at NuSI***. According to public records, Attia received an average of $425,000 per year for four years, including $727,754 in 2015, for a grand total of $1.7 million. Taubes received an average of $117,000 per year for five years, netting $586 thousand. Friedman received over $200,000 per year in 2014 and 2015, netting $495 thousand. [Update 8/22/18: After speaking with Peter Attia, I now believe there was nothing fishy about their salaries. They were set by an independent board, not by NuSI execs themselves. See this post for more detail.]

NuSI is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit corporation, meaning that its funding is explicitly intended to benefit society, not individuals. People have to make a living of course, but it’s hard to understand the rationale for a $728k salary at a nonprofit. Although Taubes’s salary appears more reasonable than Attia’s, he was writing and promoting The Case Against Sugar and doing other non-NuSI work during this time, so it appears to be for part-time work. I’m not going to come to any grand conclusions about this before hearing their side of the story, but they certainly have some explaining to do.

Here are my takeaways from the NuSI experiment, with the benefit of hindsight:

- Obesity is a difficult problem to solve. Many grand ambitions have foundered on this fact.

- As a result of NuSI’s funding, useful research was published, and more potentially useful research is forthcoming. So I don’t think it’s correct to view NuSI as a failure, despite the fact that its funding and staff have mostly evaporated.

- Certain important norms in science only work as long as everyone is behaving themselves, and this makes science fragile.

- Ideology and science don’t mix. The risk in giving ideologues power is not simply that they may fail, but that they may fundamentally corrupt science.

* One could argue that the subjects were their own controls, but ideally for this to work it should be done in counterbalanced crossover fashion with a wash-out period between diets.

** Philip Tetlock, PhD describes ideologues beautifully in his book Superforecasting. He refers to them as “hedgehogs” and pragmatists as “foxes”. Hedgehogs are persuasive because in their eyes, the world is simple and they are utterly convinced they know how it works. But they are abysmally bad at making predictions because the world isn’t as simple as they think. Most television pundits are hedgehogs and their predictions are about as good as flipping a coin. Foxes, on the other hand, understand that the world is complex and try to factor this complexity into their worldview. They learn from their mistakes. As a result, they are better at making predictions. But they get less attention because they’re less confident and their view of the world is harder to explain.

*** I initially learned about this in a post by Evelyn Kocur. I don’t endorse the aggressive tone of the post but she certainly did her homework. I have independently confirmed the salary figures in her post.

I’ve always been struck by the imprecision of how the terms “low-glycemic-index diet” and “low-glycemic-load diet” are used. In theory, these are diets that reduce post-meal blood glucose and their benefits derive from this property. In practice, they often differ from typical diets in multiple ways. If a “low-glycemic diet” is also higher in fiber and protein and/or lower in palatability, calorie density, and carbohydrate, can we really attribute its beneficial effects to its impact on blood glucose per se? To gain a better understanding of the depth and pervasiveness of this problem, I did a scientific literature search for randomized controlled trials of low-glycemic-index/load diets, selected the first ten I found, examined the details of the assigned diets, and evaluated the findings.

I’ve always been struck by the imprecision of how the terms “low-glycemic-index diet” and “low-glycemic-load diet” are used. In theory, these are diets that reduce post-meal blood glucose and their benefits derive from this property. In practice, they often differ from typical diets in multiple ways. If a “low-glycemic diet” is also higher in fiber and protein and/or lower in palatability, calorie density, and carbohydrate, can we really attribute its beneficial effects to its impact on blood glucose per se? To gain a better understanding of the depth and pervasiveness of this problem, I did a scientific literature search for randomized controlled trials of low-glycemic-index/load diets, selected the first ten I found, examined the details of the assigned diets, and evaluated the findings.